⋄ Populus ×smithii (Populus grandidentata × tremuloides),

Niobrara Hybrid Aspen (Bigtooth Aspen Quaking Aspen )

Named by Joseph Robert Bernard Boivin, description in Le Naturaliste Canadien 93(4): 435. 1966

Family: Salicaceae (Willow)

Our hybrid aspen started as a root cutting from a tree in the Niobrara valley and is one of a group then grown by Bob Henrickson of the Nebraska Statewide Arboretum "to provide an ex situ site for conservation."

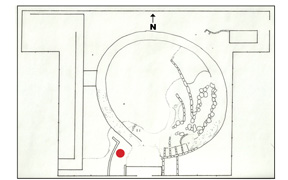

Where to find Populus ×smithii in the Keim Courtyard

SEE Source Material Related to the Niobrara Hybrid Aspens

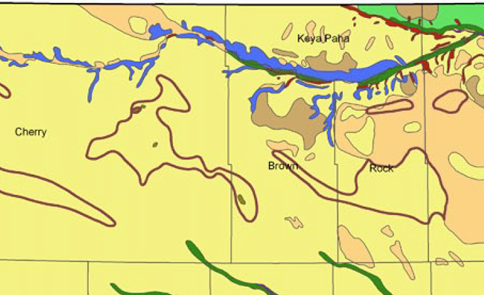

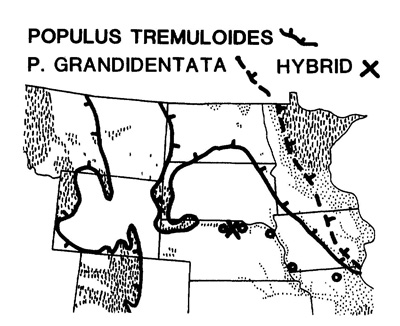

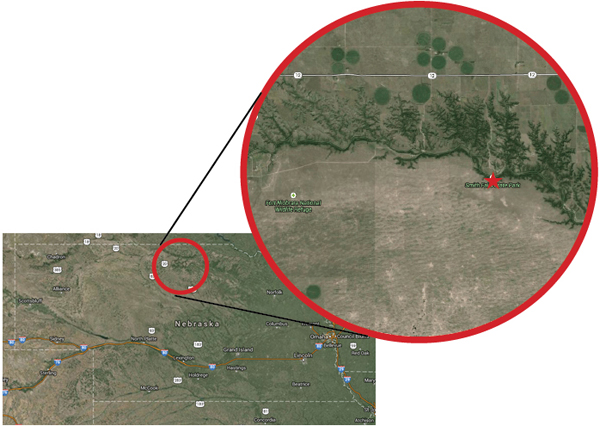

In this map detail ( Native Vegetation of Nebraska , Robert Kaul and Steven Rolfsmeier, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Conservation and Survey Division) one can clearly see the various vegetative zones present. The northern boreal forest is represented by the ice age remnants still seen on the cool northfacing canyon slopes of the river and its tributaties. The quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) is one of these relict species that has survived in small isolated pockets far to the south and east of its normal range since the retreat of the glaciers 12,000 years ago. A few hundred miles to the east, in Iowa, we find the western limit of the bigtooth aspen (Populus grandidentata). And in one specific place along the middle Niobrara River at Smith Falls there can be found a small number of a naturally occurring hybrid between these two species, Populus ×smithii.

Reproduced from Kaul, et. al. "The Niobrara River Valley, a Postglacial Migration Corridor and Refugium of Forest Plants and Animals in the Grasslands of Central North America."

Learn more/source material

Niobrara River

- Johnsgard, Paul A. The Niobrara: A River Running Through Time. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007.

- National ParkService. Niobrara National Scenic River, website .

- National Park Service. Niobrara National Scenic River: Final General Management Plan . 2006.

- National Park Service. Niobrara National River: Environmental Impact Statement . 2006.

- National Park Service. Natural Resource Program Center. Niobrara National Scenic River Condition Assessment Report . (Sunil Narumalani, Gary D. Willson, Christine K. Lockert, Paul B. T. Merani, Great Plains Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit, University of Nebraska-Lincoln) 2010.

Niobrara Valley Flora

- Bessey, Charles. "A Meeting-place for Two Floras" in Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club, 14 (1887), 189-191.

- Churchill, Steven P., Craig C. Freeman, and Gail E. Kantak. "The Vascular Flora of the Niobrara Valley Preserve and Adjacent Areas in Nebraska" in Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences 16 (1988): 1-15.

- Kantak, Gail E. and Steven P. Churchill. "The Niobrara Valley Preserve: An Inventory of a Biogeographical Crossroads" in Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies, 20 (1993) : 1-12.

- Kaul, Robert B., Gail E. Kantak, and Steven P. Churchill. "The Niobrara River Valley, a Postglacial Migration Corridor and Refugium of Forest Plants and Animals in the Grasslands of Central North America" in Botanical Review, 54 (1) (Jan. - Mar., 1988): 44-81.

Aspen Hybrids

- Pauley, Scott S. "Natural Hybridization of the Aspens" in Minnesota Forestry Notes, 47 (Jan. 15, 1946). Published as Scientific Journal Paper Series No. 3496 of the Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station.

Hybrid Aspens in Danger

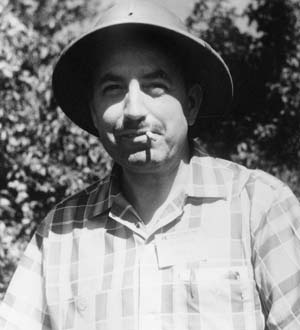

Unfortunately, climate change and other factors are threathening this singular population of hybrid aspens at Smith Falls as well as the paper birch that grow in the Niobrara River valley. While a number of people and organizations are concerned about the fate of the aspens, ecologist and founder of the Western Nebraska Resources Council "Buffalo" Bruce McIntosh's dedication is perhaps of a different order. In recognition of his work to protect and restore the aspens of the Niobrara valley, in 2011 Bruce received the Conservationist of the Year Award from the Nebraska Wildlife Federation. In this video you can listen to Bruce explain the importance of saving the aspen and see his work with a group of volunteers to clear encroaching red cedars from the aspen habitat:

Watch a video about Bruce's work with volunteers to save the Niobrara's hybrid aspen

From the Omaha World Herald:

VALENTINE, Neb. — They shouldn't be in Nebraska.

Corn grows here. Prairie grass grows here. Summer is hot here.

But tucked away in a few sheltered niches of Nebraska's Great Plains are shimmering prehistoric gems that defy explanation — aspen trees. These trees, known for their white bark and gold autumn leaves, are typically thought of as iconic symbols of the Rocky Mountains or northwoods lakes. Nebraska's relics, however, are natives, survivors of the spruce and fir forests that cropped up after the last glaciers retreated more than 10,000 years ago. They survived changing climates over millennia. They survived prairie fires. They survived settlers. Now some of these lonesome clusters are in peril.

Their 21st century enemies are encroachment by other trees and roaming cattle. "Many of the aspen trees along the (Niobrara) river are unhealthy or have died," said Stuart Schneider, chief ranger for the Niobrara National Scenic River near Valentine in north-central Nebraska. "We're concerned the aspen could vanish from the Niobrara valley."

Seventy miles south of the Niobrara groves, an isolated cluster of aspens on a Sand Hills dune outside the Nebraska National Forest near Thedford is under extreme stress from livestock degradation, said Bruce McIntosh of Chadron, an ecologist with the Western Nebraska Resources Council. "They're living on the edge," McIntosh said. "They're something that logically shouldn't be there, and they might not be there for long."

McIntosh said cattle walking on eroded trails through the grove are slicing shallow roots that bring water to the trees, perched midway up the side of a towering grass-covered dune. The grove was vibrant as recently as 2006, he said. Talks are under way with the landowner to fence and protect the trees, McIntosh said. Nebraska's small population of native aspens is generally found in three areas — the Pine Ridge in the northwest corner of the state, in and around Smith Falls State Park in the Niobrara valley and two places in the Sand Hills: Valentine National Wildlife Refuge and outside the Nebraska National Forest's Bessey Ranger District.

A fourth aspen site northeast of Halsey was wiped out by eastern red cedar encroachment in recent years. The tallest native aspen in Nebraska's record books is a 60-foot tree near South Sioux City in the northeast corner of the state.

Pine Ridge aspen are found in about 20 stands from Hay Springs west to the Wyoming border, McIntosh said. These are quaking aspen, like those found in the Black Hills and the Rocky Mountains. The Bessey and Valentine refuge stands also are quaking aspen. Smith Falls' aspen are a rare hybrid of western quaking and eastern big-tooth species.

Schneider said government agencies and landowners grew concerned about the health of the Smith Falls aspen in 2006. Several groves in the cool side canyons of the Niobrara's south bank showed signs of poor health caused by overcrowding, drought and, possibly, increased summer temperatures. Lack of sunlight reduced the trees' vigor. A century of fire suppression created an unhealthy forest along the banks of the Niobrara. Ponderosa pine densities are unnaturally high. Invasive cedar is the dominant tree.

Crews led by the park service, Nebraska Game and Parks Commission and the Nature Conservancy are in their second year of a project to remove competing oak, ash, box elder and other trees and vegetation that steal sunlight from the Niobrara site's 15 to 18 aspen groves. Some groves have only one or two trees. Others have about 30 trees. Jim Luchsinger, director of the Nature Conservancy's Middle Niobrara Program, credited McIntosh with launching the fledgling aspen rescue efforts.

"Until Bruce came along, frankly, our aspens were something we were worried about. We wanted to do something, but we just didn't have the resources,'' Luchsinger said. McIntosh cobbled together volunteers and coordinated the thinning of invasive trees from aspen groves on Nature Conservancy land.

Early results of the thinning project are encouraging, Schneider said. Aspen sprouts that emerged from areas cleared last year were hit hard by insects and other creatures. Ninety percent of the sprouts didn't make it. But 10 percent survived. "That's a lot better than zero,'' Schneider said.

Officials plan to meet soon to discuss conducting a controlled fire in the aspen groves next year to destroy remaining invasive trees and reinvigorate the aspen groves. Botanists will monitor the sites for decades to chart survival rates and reproduction.

"These rare hybrid aspen are near and dear to us, and we want to try to keep them here,'' Schneider said. The threatened Bessey grove was noted in University of Nebraska botanist Raymond Pool's 1919 "Handbook of Nebraska Trees'' and then largely forgotten. McIntosh learned about the grove from Greg Schenbeck, a Game and Parks Commission biologist at Chadron.

Schenbeck rediscovered the stand in 1988 when tracking a sharp-tailed grouse hen during a nesting research project for the U.S. Forest Service. "To be in the middle of the Sand Hills and stumble across an aspen patch halfway up a big dune and absolutely no evidence of an old homestead totally blew me away," Schenbeck said. "There were a zillion suckers coming up. It was in very good shape."

McIntosh recently gathered leaf samples from the Bessey grove and other aspens across the state for a genetics study. Results are expected later this year. The Bessey grove explodes with biological diversity despite its isolation in the middle of the Sand Hills, a 20,000-square-mile grassland that covers one-quarter of Nebraska. McIntosh has seen a rare pale swallowtail butterfly, tree locusts and locust wasps among the trees.

"That's what makes them so unique and worthy of preserving and study," he said. "It's an enchanted forest."