About Oaks | Map | Plant List | Arboretum Species/Cultivar Information | Sources | Other Campus Oaks of Interest

“Eros shook my mind like a mountain wind falling on oak trees” — Sappho, Frag. 47

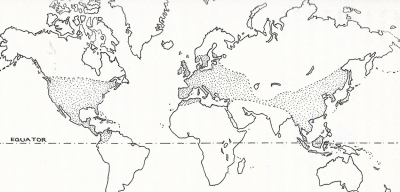

WORLD OAK DISTRIBUTION

Introduction

Where to even begin when talking about oaks?

The literature about them is so vast, it's overwhelming. Their presence, if not in our lives, at least in our minds—and in our hearts—is as substantial as their trunks, as far-reaching as their branches, as deeply-rooted as, well, their roots. Little kids know about them from their iconic fruits, the impossibly metaphoric acorn. Poets, from Sappho (“Eros shook my mind like a mountain wind falling on oak trees”) to the present, explore every aspect of the tree. Americans have chosen the oak as our national tree. But the British are obsessed, absolutely oak-identified and the oak as a symbol of Britain dates back hundreds of years. Their fruits and leaves have found their place in sculpture and painting from China to Rome. They occupy our deep-psyches and erupt through myth and story the world over—well, the Northern Hemisphere, at least. Their wood houses us, allows nations to conquer the world. Their fruits feed us. They also sustain, give refuge to, and feed more non-human animals (mammals, insects, birds), fungus, and lichens than any other plant. Oaks are essential.

What's in a Name?

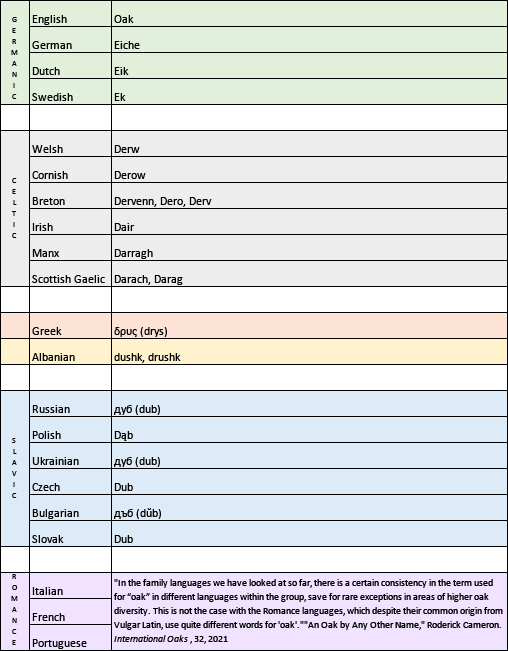

"OAK," in almost every European language, can be traced back to only four Proto-Indo-European roots. This includes the Germanic, Celtic, Romance, and Balto-Slavic language families, as well as the stand-alones Greek and Albanian. The word, in whatever language, is old, fundamental, and foundational. [click to acccess PDF of European words for "oak"]: . © Levine UNL

. © Levine UNL

For a fascinating detailed analysis of the origins of European words for "oak," see "An Oak by Any Other Name" by Roderick Cameron (from the International Oak Society journal). See also Paul Friedrich's Proto-Indo-European Trees: The Arboreal System of a Prehistoric People (University of Chicago Press, 1970).

The generic name Quercus, the ancient Romans word for "oak" in Latin, descends from the Proto Indo-European root *perkw. We have Carl von Linné (Linnæus) for designating oaks as Quercus in his 1753 Species Plantarum. He identified fourteen types of oaks.

But what did the indigenous people of Nebraska call our native oaks?

| TREE | ACORN | |

| OTO-MISSOURIA | But'uinge Oak (possibly just Bur Oak) Tašgu Náthewe (Blackjack Oak) Dhíku (White Oak) |

Buje |

| OMAHA-PONCA | Táshkahi (Bur Oak) Buude-hi (Red Oak) |

Búde |

| PAWNEE | Ckaárus Patki-natawawi (Bur Oak) Nataha-pahat (Red Oak) |

Pátki Patkickuusuʾ (acorn shell) |

| LAKOTA |

Útahu cȟaŋ (acorn + stem + tree) |

Úta |

Taxonomy

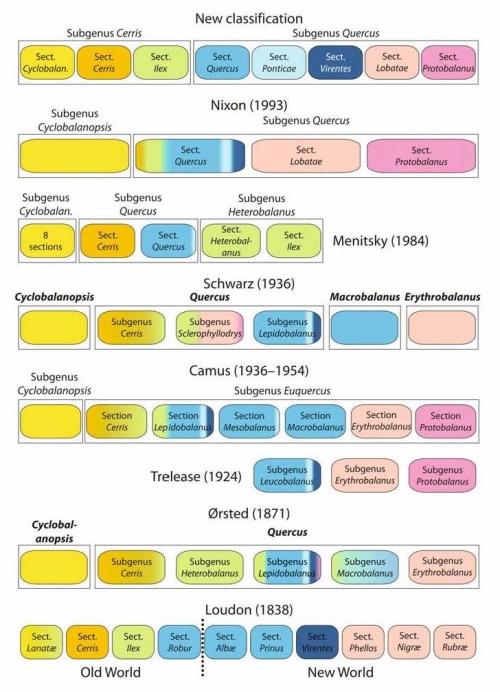

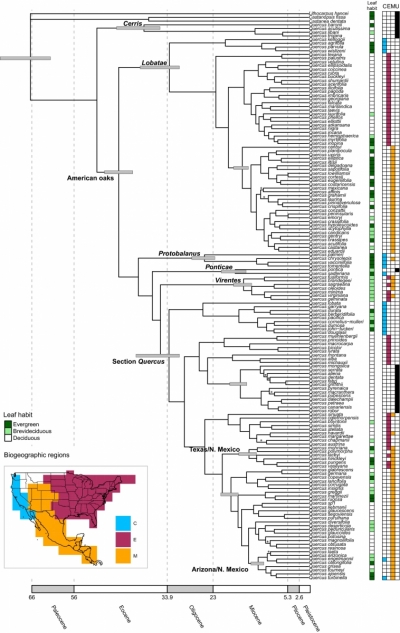

There are over 400 species of oaks in the Northern Hemisphere, 260 in North America alone. Oak taxonomy is complex—seemingly in constant flux, being reassessed, reorganized.

This chart shows only some of the Oak classification systems over the past 180+ years:

From "An updated infrageneric classification of the oaks: review of previous

From "An updated infrageneric classification of the oaks: review of previous

taxonomic schemes and synthesis of evolutionary patterns."

Thomas Denk, Guido W. Grimm, Paul S. Manos, Min Deng & Andrew Hipp.

If you're interested, check out the latest classification of the Red and White Oaks of North America, hot off the press (June 2021):

The paper, "An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks (Quercus Subgenus Quercus): Review of the Contribution of Phylogenomic Data to Biogeography and Species Diversity," by Paul S. Manos and Andrew L. Hipp is available here.

Additional oak organization systems—simple and not-so-simple—for the world's Quercus are available on line.

All but one of our oaks in the arboretum and on campus belong to these two groups or sections:

| RED OAKS section Lobatae |

WHITE OAKS section Quercus |

| Acorns mature in two seasons | Acorns mature in one season |

| Pointed lobes with bristled tips | Rounded lobes, no bristles |

| No tyloses | Tyloses** https://www.indefenseofplants.com/blog/2017/9/19/red-or-white?rq=oaks |

| Acorn cap inner surface has tiny hairs |

Acorn cap inner surface hairless or almost |

Evolution

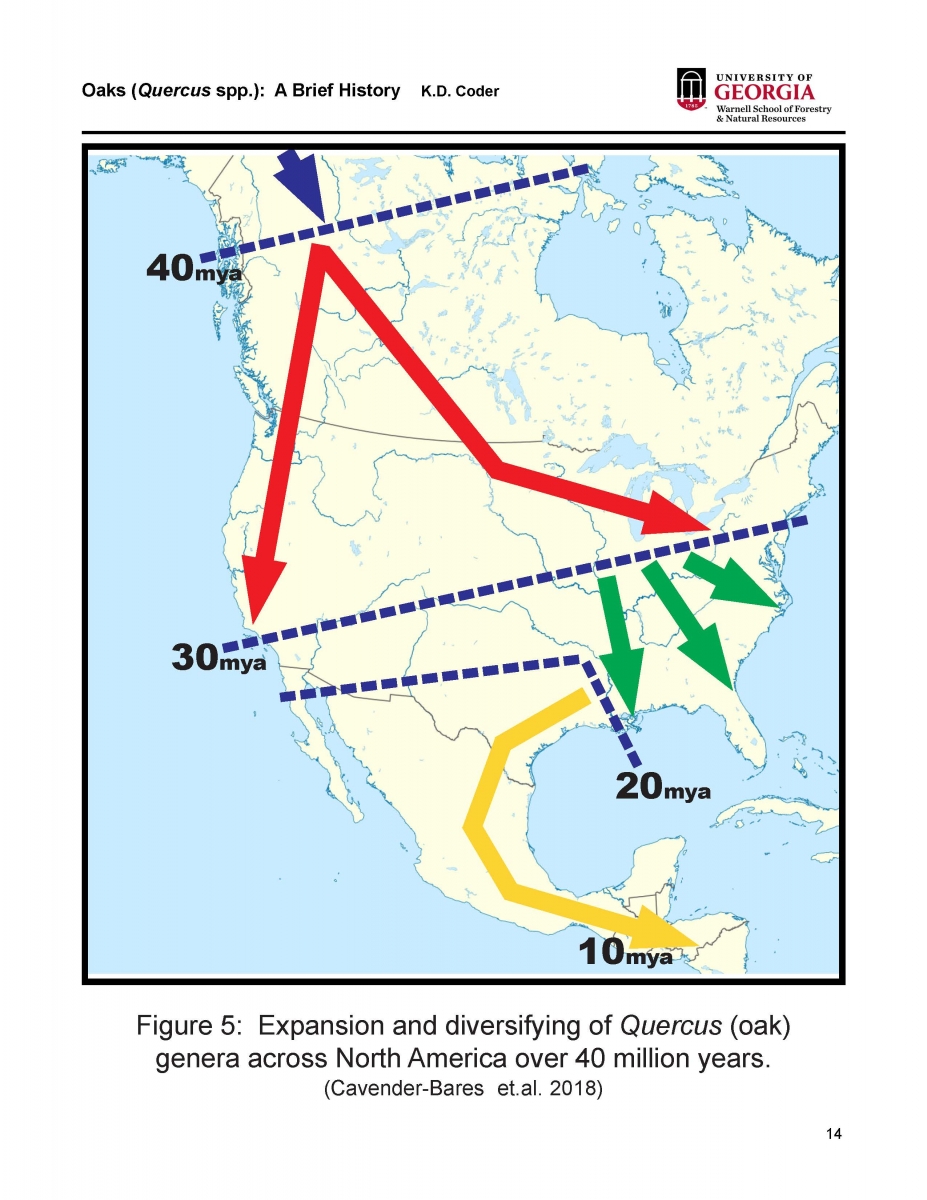

What we would recognize as oaks today appeared around northern latitudes 55 million years ago, decendents of European beeches. Our North American White Oak and Red Oak groups developed in what is now the boreal forest zone during a period of relative warming. Over millions of years, they moved south, spreading across the United States and into Mexico. (Click the chart to access PDF.)

From "Sympatric parallel diversification of major oak clades in the Americas and the origins of Mexican species diversity."

Andrew L. Hipp et. al., New Phytologist, 217:1 (Jan. 2018). https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14773

Their wanderings, responses to glaciation, divergence into the two main groups, and the development of the species are clearly outlined in Dr. Kim D. Coder's "Oaks (Quercus spp.): A Brief History." Coder distills a complex subject and makes it accessible to the lay reader. Her large clear charts and maps will help you to understand the development of North American oaks.

◊ Check out this great 2004 issue of the Nebraska Statewide Arboretum's "The Seed" all about oaks. With contributions from Jim Locklear, Justin Evertson, Guy Sternberg (founding member of the International Oak Society), and Bob Henrickson.

R=Red Oak Group, W=White Oak Group; LC=Lancaster County native, NE=Nebraska native, US=United States native