About | Plant Map: JPG PDF | Plant Information | Collection Quick Guide: Excel PDF | Bibilography

Even though they can play a useful role in the garden and fill an important niche, as landscape plants vines are underutilized design components of height and verticality and are often neglected by landscape architects and homeowners alike. People tend to focus on herbaceous plants—which they think of as “flowers”—and woody plants— that they limit to trees and shrubs. Vines, whether herbaceous or woody, somehow get lost.

Vines are characterized by fast growth and limited lateral growth (although there are notable exceptions). They can be deciduous or evergreen, monoecious or dioecious, ten feet or a hundred.

Vines are plants that do not support themselves but scramble or climb upon others. They are an evolutionary adaption that developed independently in numerous plant families.

For what purpose?

Why dedicate energy to growing upright with a sturdy and rigid stem/trunk when you can take advantage of other plants to do that work for you? The great lianas of the rain forest (think the long ropey vines in Tarzan) reach the sunlit canopy by piggy-backing on giant forest trees.

How do vines accomplish this? How do they climb?

They have developed a number of different strategies, sometimes using more than one of these strategies at the same time, and sometimes modifying a prefered strategy depending on the available support structure.

These various strategies have fascinated people in many fields of study for a long time. The mechanics of twining and tendrils especially are complex and have been the focus of experimentation and entire books dating back to Darwin. His "On the Movements and Habits of Climbing Plants" was originally published in the Journal of the Linnean Society of London, 1865, 9: 1-118 and later published seperately as a monograph. More recently, in-depth scientific explorations like The Biology of Vines (ed. Putz and Mooney, Cambridge University Press, 1991) have appeared.

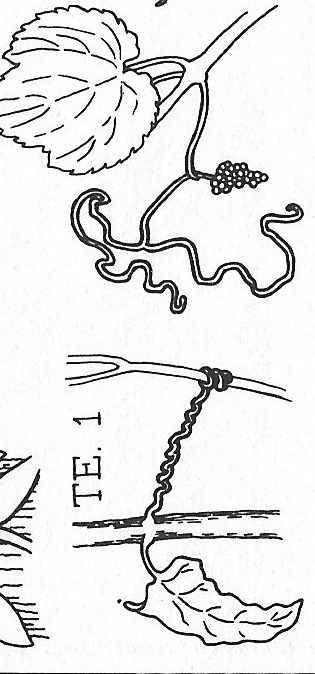

Scientists study just how twining vines twine, in which direction they spiral, what the angle of their spiraling is, and how large a center structure they can spiral around, among other things. They study how tendrils reach out searching for something to grab onto, moving around in mid-air until they come upon something of the right diameter to meet their needs for attachment. Time lapse videos of both of these mobile strategies are fascinating to watch and provide scientists with detailed information on these complicated processes.

☞ Support Structures

Because of vines' varying growth habits and attachment strategies, it is crucial to provide the right kind of support for each particular vine. Do you need a wall or large post for adhesive pads or adventitious roots? Wire for tendrils? Posts of varying dimensions for different twining vines?

Whatever vine you have or are considering purchasing, be sure you can give it what it needs to do what it does.

Conversely, if you have a certain structure, whether it be a trellis, a wall, or a post, and you want to grow a vine on it, be sure to select a vine with compatible support needs.

☞ Attachment Strategies

Scroll down for images and explanation of various support strategies

☞ Maxwell Arboretum Vines

Scroll down for information & images of each vine in the Arbor.

Dedication of the original Vine Arbor, May 1990

__________________________________________________________________________________

ATTACHMENT STRATEGIES INCLUDE:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

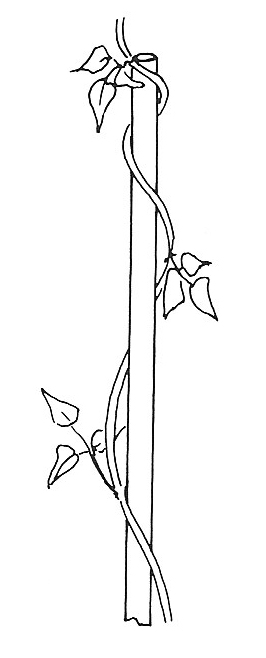

Twining (bines) |

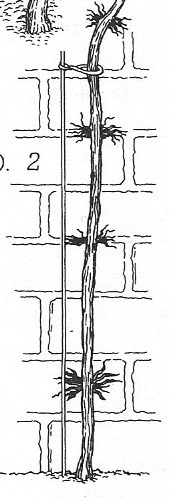

Adhesive Roots Along the underside of its stems, the vine sprouts roots that can cling to small surface bumps on trees, rocks, and man-made structures. Once the roots are in place, they secrete a glue-like substance to adhere to the surface. |

Tendrils |

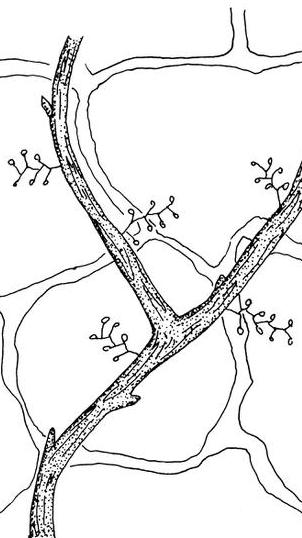

Adhesive Pads or Holdfasts: at the ends of tendrils. Like root climbers, lianas that have adhesive tendrils adhere to the tree or surface that they are climbing. However, it is not the roots that are doing the climbing in this case, but modified tendrils that have small adhesive pads at the tips. |

Hooks |

The following plants are found in the Maxwell Arboretum Vine Arbor (click to access information, location map, and photos)

| SCIENTIFIC NAME | CULTIVAR | COMMON NAME |

| Actinidia kolomitka | 'Arctic Beauty' | Hardy Kiwi |

| Akebia quinata | 'Shirobana' | Fiveleaf Akebia |

| Akebia × pentaphylla | Fiveleaf Akebia | |

| Celastrus scandens | American Bittersweet | |

| Clematis | 'Proteus' | Clematis |

| Clematis | 'Rouge Cardinal' | Clematis |

| Clematis terniflora | Sweet Autumn Clematis | |

| Clematis texensis | 'Princess Diana' | Clematis |

| Hydrangea anomala petiolaris | Climbing Hydrangea | |

| Lathyrus latifolius | 'Pink Pearl' | Sweet Pea |

| Lonicera × heckrottii | 'Summer King' | Gold Flame Honeysuckle |

| Schisandra chinensis | Magnolia Vine | |

| Wisteria frutescens | American Wisteria | |

| Wisteria frutescens | 'Aunt Maude' | American Wisteria |